Cartographic Justice: From Omission to Illumination of America’s Black Communities

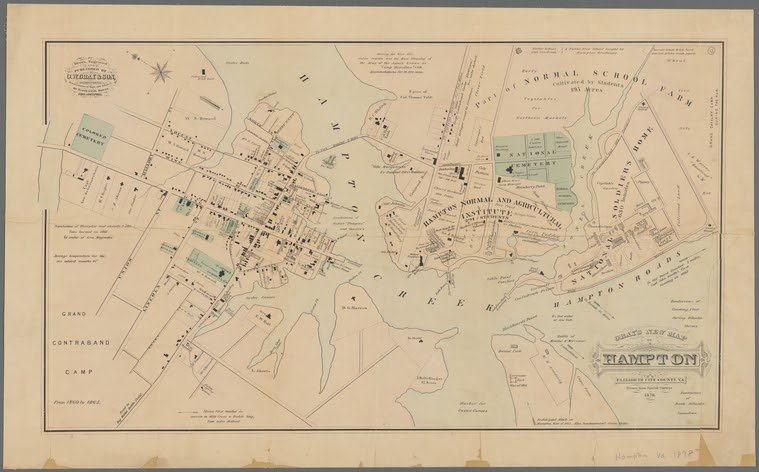

I was struck one workday by a 1878 map I picked up entitled Gray’s New Map of Hampton, depicting Hampton, Virginia, in the decade after the Civil War (Fig. 1). The image shows the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, then an agricultural and teachers’ college for Black students, now known as Hampton University. The city’s Black population is referenced through "colored" institutions like cemeteries and churches, but individual names of homes or buildings are only labeled for white businessmen, such as George Dixon’s oyster house visible by the Hampton Creek steamboat landing.

I would probably not have given much thought to this disparity in representation, assuming it merely to be the harsh economic reality of a segregated Southern city where poor Black people labored for white businessmen, except that I had just finished reading Robert Engs’s Freedom's First Generation: Black Hampton, Virginia, 1861-1890. I knew from Eng’s careful archival study of the history of Hampton and its eponymous university that the map’s lack of detail was in fact a purposeful omission designed to obscure the prominence of Hampton’s Black community during Reconstruction. Though Gray’s map situates a crowded mass of buildings labeled only as “Stores” at the intersection of King Street and Queen Street—despite offering detailed names for the other blocks’ buildings—Engs reveals that Black-owned businesses and homes filled this area. Furthermore, the 1880 census shows that the vast majority of Hampton’s Black workers were professionals and skilled laborers. Only one percent of Black laborers served as farm workers, despite the map’s emphasis on agrarian work in the surrounding fields. In fact, though white Northern businessmen are credited with starting the oyster industry in Hampton, the census also indicates that many of the skilled laborers were Black oystermen and teamsters, independent workers who often owned their boats and trucks. Black people held significant business clout in this town; why did the map make it seem as if only white people did?

Because I’m a reference librarian in a map collection, I know that no map is truly objective. Maps are often lies, but even then, they can teach us things that are true.

Why Gray decided to omit Black businesses from his map is simple: it sold well. Ormando Willis Gray was a successful Philadelphia publisher whose highly-collected atlases (and individual maps therein) were produced as the country was expanding territorially and economically to unprecedented extremes after the Civil War. These phone book precursors offered geographic updates, complete with business names and locations, for a mushrooming white consumer class. In purchasing atlases like Gray’s, they bought a vision of a country where all the prosperous people looked like them, and everyone else assimilated to their norms. Despite my training, I almost fell for the facade too. I only caught the distortion because of my extensive research on this map, among others, for an exhibition I curated about maps of American food history. The seafood industry was my ticket into a story I didn’t know I would find.

There are at least three broad categories that information professionals like me should be using as starting points for telling the real story behind our collections.

First, we must actively seek out ignored or erased Black and Indigenous histories among our collections. The fact that I knew what was going on in Hampton was fortunate, but how many other histories have I missed, or have colleagues of mine missed? Until we fully accept that all maps are hiding the truth from us, and that their claims always have to be challenged, we’ll keep perpetuating marginalization.

That brings us to the second category: becoming well versed in—rather than just vaguely aware of—the work of Black and Indigenous scholars, who for centuries have been telling their own history, as well as their present and future, as public historians and land protectors.

Black archivists and librarians such as Bergis Jules have been working steadily to hold white professionals like me, and the institutions we work for, accountable for ways we perpetuate injustice. A myriad of community-driven projects now amplify Black voices previously confined to the margins, if included at all, in traditional archives. Organizations like the Digital Public Library of America are hosting such endeavours. And institutions complicit in that marginalization are beginning to course correct for equitable representation, as demonstrated by the 2020-21 digitization schedule at Harvard’s Houghton Library.

The third category is that we have to check—again and again—our assumptions and “default settings.” I almost misinterpreted Hampton’s history even though I actively work on race and justice in historic materials.

In 2020, the people whose ancestors have long been erased from authoritative maps are now drawing and redrawing them, en route to being properly represented within their boundaries. Black mapmakers are synthesizing new maps much more inclusive than Gray’s, which I see as a form of cartographic justice.

A particularly moving example is the COVID Black Stories map from the COVID Black taskforce’s Homegoing Digital Memorial project (under the direction of Dr. Kim Gallon), which gives names, occupations, and obituaries of Black people who have died from COVID-19 as a visual counterpoint to the more common epidemiological maps that remove the individuality of those infected. It would be exciting to see a Black Geographies practitioner similarly reframe Gray’s map of Hampton, using archival data to restore the presence of that city’s nineteenth-century Black entrepreneurs.

It feels fitting to end, however, with a more jubilant recent example: the November 3rd electoral result map of Georgia. In 2020, Black women organizers like Stacey Abrams "flipped" the state of Georgia by enfranchising record numbers of people, especially Black people, to vote. All academic projects aside, the very best thing that white librarians like me can do is to support these efforts with our labor, our finances, and our professional practices of citation. It is most certainly the right thing to do, and a way that all information professionals can support and move towards cartographic justice.